By Shayla Croteau, Automotive Hall of Fame intern

Helene Rother, hired by Harley Earle in 1942, was the first woman in the General Motors design studio and one of four 2020/2021 Inductees at the Automotive Hall of Fame.

Rother went on to establish her own design studio in 1947 and was quickly contracted by Nash-Kelvinator as a design consultant. From 1948 to 1956, she designed most of the interiors seen in Nash vehicles, bringing color and elegance to the automotive industry.

In preparation for Rother’s induction, historians at the Hall have been intensively researching her highly successful career in automotive design. In the process, we met Francesca Steele, the author of an authoritative Hemmings article on Rother’s journey.

Our conversation with Steele led to the discovery that she had transcribed a scanned copy of Rother’s typed and hand-annotated speech provided by the Society of Automotive Engineers International (SAE), and with their approval, Steele graciously shared the transcription of one of the most valuable extant primary source pieces on Rother: the speech she delivered to SAE annual meeting in 1948. The speech, “Are We Doing a Good Job in our Car Interiors?” marks the first time that a woman addressed the SAE.

Steele has a degree in Art History, Criticism, and Conservation from the University of California, Berkeley. She grew up watching her father restore cars and build café racing motorcycles for her brothers to race, and she has restored several vintage American automobiles herself. The collision of these two interests provides Steele with a unique perspective and skill set for writing on automotive history, and she has found a passion for highlighting women in the industry. Along with the Rother article, Steele has written several other pieces for Hemmings. She states, “I think in order to bring women into the automotive field of information, you have to paint bigger pictures and more colorful stories and give them personalities.”

Although Steele’s focus is on journalistic writing, her research often necessitates that she become a transcriber as well. This was the case with the 1948 speech, which Steele acquired in nearly illegible condition. Steele said, “It depends on the piece if I’m going to pay for it or not. This one, I needed it. I really wanted to hear Helene’s words, as she wrote them, as she gave that speech.” Steele decided that she would be the one to transcribe the speech and ensure that Rother’s words would not be lost to history.

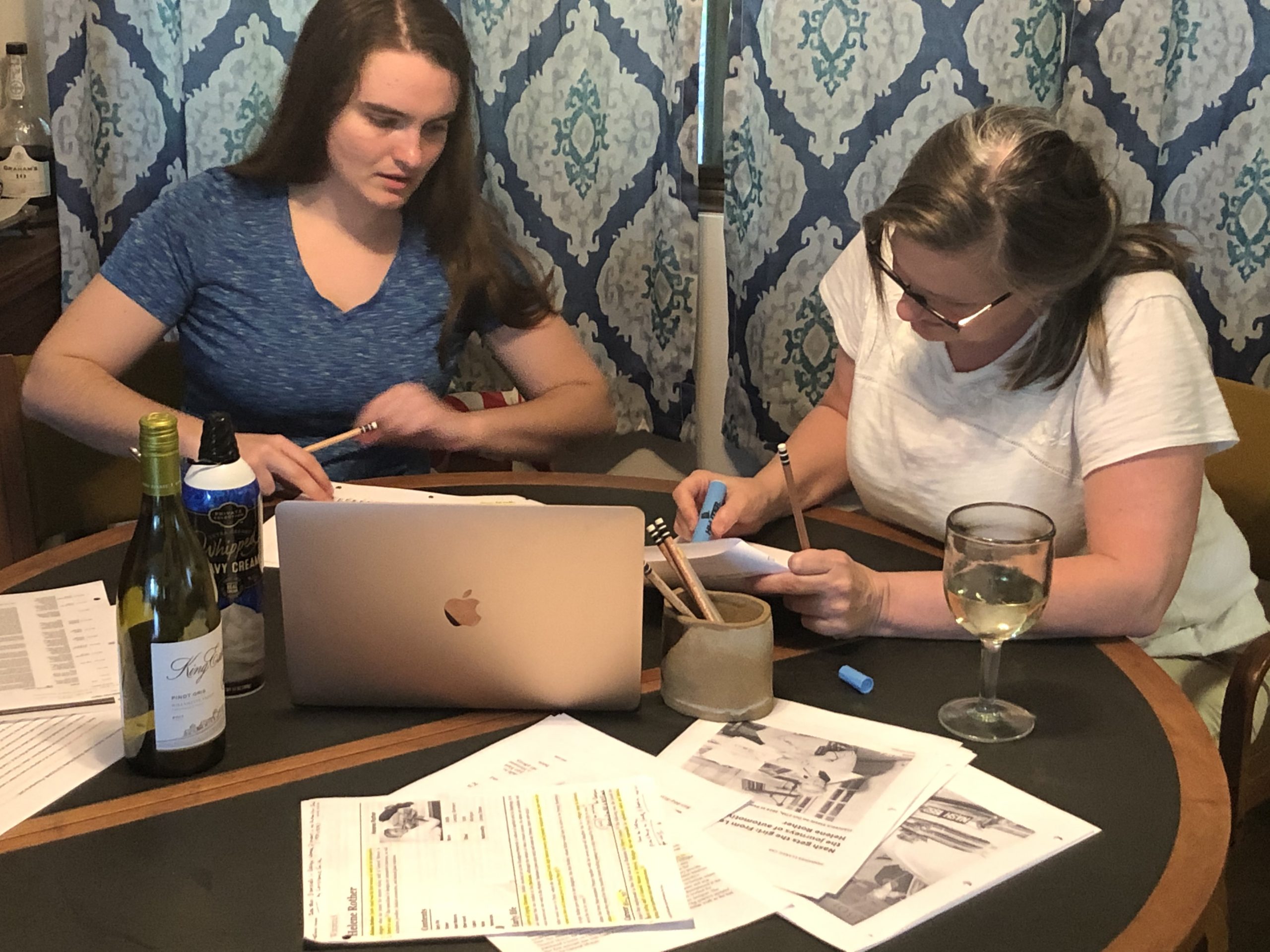

Steele began the transcription on her own, patiently trying to make out the indecipherable words. After several hours of work, she recruited her daughter, Roxanne Pelton, to assist in the undertaking. Pelton, a current law student with a background in physics, brought a different skill set to the table. She suggested running groups of letters through bots, but the approach was met with little success. Steele says, “Everything was a blank- the bots couldn’t read it at all!” Steele and Pelton then tried crossword puzzle programs, which unscrambled several of their problematic words. Steele explains Roxanne’s use of such programs, saying, “The programs that she found on crossword puzzles – she was able to throw in words, and combinations of words, and sizes of words … that’s how she was able to get all the words that I couldn’t get. So it was definitely a joint effort.”

Once the pair had transcribed the majority of the document, they were able to understand what Rother had communicated to the SAE. “It seemed that the theme of it was color,” Steele states. “She was interested in relaying to the engineers and to the people that were there that the colors of the automobiles … that they were outdated, that they had an opportunity there. She had done all this independent research, and so she was presenting this idea that there could be change, there could be something dynamic … as an independent designer, she could bring something unique to an exploding market that was just right on the horizon after the war.”

Steele estimates that she and her daughter spent about 20 hours, between the two of them, to get the seven-page speech transcribed into its current state. When they shared the piece with the Hall, there were just a few words left that were considered good guesses, but uncertain. One of these words, “vaguefully,” stumped the pair during transcription because it seemed like a made-up word. After some research, they found that it was actually a commonly-used word during the 1920s that has since fallen out of use.

Another word, “emissive,” caused Steele and Pelton problems because it was used in an unusual context. On page six of her speech, Rother states, “Lightness is the aristocracy of mechanical technology. Lightness, effortlessness and simplicity must be the basic considerations of our automotive designs. A speedometer which looks like a cash register is out-of date. So are the emissive buttons and complicated ornaments, vaguefully designed to bruise knees and elbows! We will need much less chrome but we will be forced to find better metal finishings, more exciting complications and contrasts of colors, textures, and designs.”

Even after hours of transcribing Rother’s words, Steele is not yet completely satisfied with her work. She noted several names mentioned by Rother, saying, “I’m still not really sure about them, but I’ll just keep digging into it a little bit. So, there’s still a little bit more work to do to the document.” Despite the few loose ends left for Steele to tackle, Rother’s speech has proven itself an invaluable source of information for the Hall. You can read Steele and Pelton’s current transcription of the speech here, and learn more about Helene Rother here.

The Automotive Hall of Fame is grateful for the donation of the transcription of this speech by Francesca Steele and Roxanne Pelton from the original, which is preserved within the Society of Automotive Engineers International Mobility History Archives and used with their permission.